I regularly read an article that I enjoy reading and that I find relevant for psychotherapy. I summarize it and discuss how I see it as relevant for clients on my blog. Do you have questions, comments, or suggestions for other articles to read? Leave a comment below the post.

Discussion of The Sudden Devotion Emotion: Kama Muta and the Cultural Practices Whose Function Is To Evoke It

In their article The Sudden Devotion Emotion: Kama Muta and the Cultural Practices Whose Function Is To Evoke It, Dr. Fiske and colleagues discuss the emotion kama muta, which in Sanskrit means ‘moved by love’. They explain that we can recognize this emotion when we suddenly experience an intensification of feeling a sense of trust, care, and belongingness. The authors suggest that the function of kama muta is to make us engage in acts of commitment with those around us. I think that experiencing kama muta pulls us closer to others, makes us more committed to others, and thereby makes us more responsive to others (if you want to know about responsiveness, I discuss it in a previous blog post).

Although we experience a positive feeling when we experience kama muta, the authors reason that kama muta is an emotion that usually arises in a background of loss and longing. For that reason kama muta can be evoked in combination with other negative emotions (e.g., sadness) and various negative life events (e.g., the loss of a loved one).

But how do we know if what we are experiencing is indeed kama muta? A way to recognize emotions is to identify the physical sensations that accompany kama muta. In other, related work, Dr. Fiske and colleagues found that when we experience kama muta, we feel warmth in our chest, goosebumps, and teary eyes (but of course, even though these physical sensations commonly occur when we experience kama muta, one can also experience kama muta without these physical sensations; this is in part the complexity of our emotional lives).

As Dr. Fiske and colleagues described in their review, we may experience kama muta without any particular effort coming from another person (e.g., when we think about someone we love). We may also feel it when someone has a very generous act towards us (e.g., a stranger kindly helping us) or when there is a lot of effort involved until it culminates in an emotional encounter (e.g., the moment a father hugs a son that arrived from fighting in the war). Finally, it is also possible to experience kama muta simply by witnessing the intensification of a relationship bond between other people (e.g., watching an emotional marriage proposal).

Implications for clients I see in therapy

When clients with a history of childhood trauma imagine themselves taking care of their younger selves, this is a moment that I usually see my clients experience kama muta. Or when one partner in couples therapy shares their most vulnerable feeling of not being good enough to their partner, when they get to open their hearts it often evokes kama muta in both of them. When I witness these moving (imagined or real) encounters, I too feel the warmth in my chest and the goosebumps on my arms both typical from kama muta.

I understand that kama muta may have a function in therapy, which is to give clients the sense of security with me. This security can help them change the way they relate to themselves and others. I suspect that the sense of belongingness evoked by kama muta helps my clients better regulate their fears. As I mentioned in my previous post, when we trust that others will be there for us we feel safe and we are better able to have our needs met. As a therapist, I hope to make my clients feel safe to explore the resources they carry inside them and that they may find in their relationships.

Limitations in Applying the Study to Therapy and Conclusion

Given the definitions Dr. Fiske and colleagues used to define kama muta, I associated this emotion with the concepts of perceived social support and responsiveness. Nevertheless, the authors do not refer to these concepts in their study and the link is therefore quite tentative, from a research point of view. I am interpreting what they found as a therapist and what I see with my clients.

Another limitation is the complexity of interpreting the emotion someone feels and what they show outwardly. How easy is it for me as a therapist – particularly at this stage of this research program – to figure out whether someone is experiencing kama muta or not? The tears I see coming from my clients eyes when they seem to feel touched could simply signal sadness instead. It takes joint effort by client and therapist to understand what the client is going through.

This emotional background of loss and longing present in kama muta is also present in psychotherapy. When people come to therapy, they expect to find something they miss in their lives and in their relationships. I believe that the empathic concern people feel when they experience kama muta can be a key ingredient for change during psychotherapy. I suspect that kama muta can well be a key ingredient in fostering a sense of trust that may help people shift the way they see themselves and others.

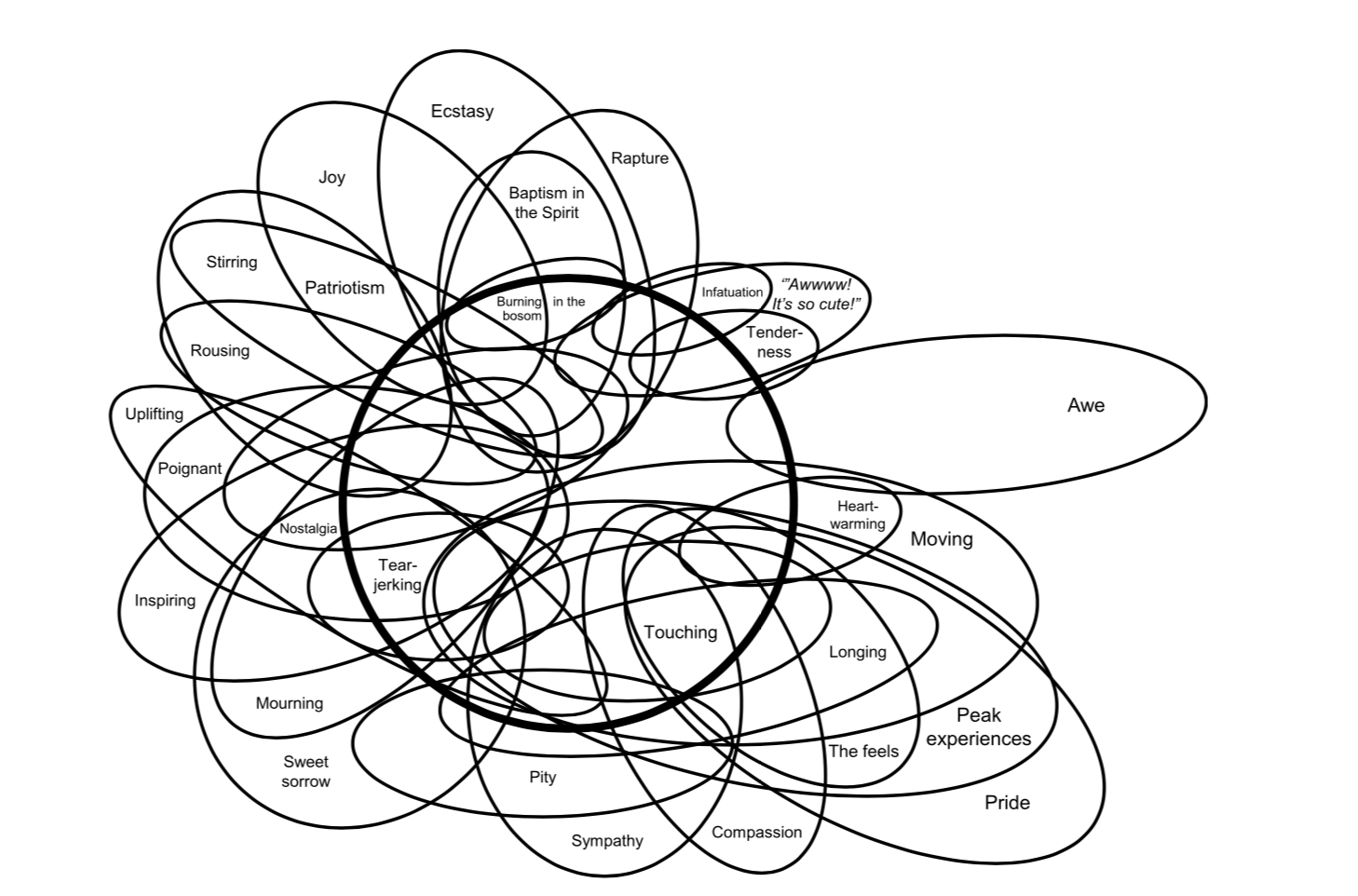

Image from the article The Sudden Devotion Emotion: Kama Muta and the Cultural Practices Whose Function Is To Evoke It